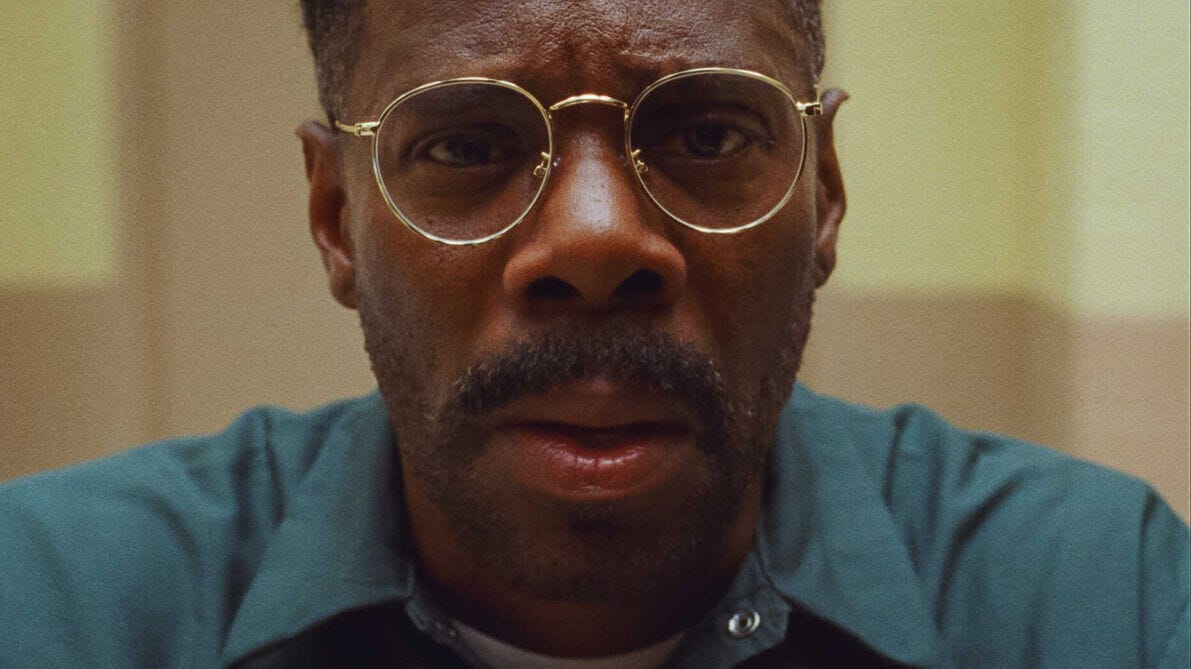

Colman Domingo masterfully brings the haunted inmate “Divine G” to life

Sing Sing (2023)

In theaters

“Rehabilitation” is on the agenda of many correctional institutions, but their administrators admit that success in that area is provisional at best. Dispiritingly, recidivism among inmates hovers around 60%. For those who’ve gone through the RTA program, however, it’s 3%.

Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) was founded in 1996 at Sing Sing, the New York maximum security correctional facility. This movie, set in 2005, convincingly takes us within that institution and program.

Prison grit – harsh treatment of inmates, prisoners at each other’s throats, combustible violence – is glimpsed here but doesn’t overwhelm the men we meet. Of course, they’re not immune. Does anyone use the word “safe” to describe life behind bars?

Yes, actually. There are safe spaces, even in the harshest holding fortresses. We get to explore one here, through a committed group of inmates supported by RTA.

That program, still thriving, allows inmates to stage plays for the prison population and invited guests.

Staying true to the actual program, Sing Sing Director Greg Kwedar uses only a handful of professional actors. The rest are alumni of the program or other former inmates, largely playing themselves. It’s their growth, through art, that the movie explores and celebrates.

Yet it also wants to tell a compelling story about struggling individuals, and it takes the risky path of mixing professional actors with former offenders, non-actors relying on their experience behind bars to shape and deepen their performances.

The most prominent professional is Oscar nominee Colman Domingo as the inmate John Whitfield, known as “Divine G”. Sentenced to 25-to-life for a murder he didn’t commit, he’s become a loner/intellectual behind bars.

On a typewriter in his cramped but neatly kept cell, lined with books, he composes plays RTA has sometimes put on. He’s also a bit of a jailhouse “lawyer”, helping inmates research strategies to earn them parole. His own next parole hearing, the latest in an unsuccessful string, is due shortly.

The other seasoned actor in the cast is Sound of Metal Oscar-nominee Paul Raci playing Brent, the RTA’s director/facilitator. Brent isn’t an inmate but a theater veteran wise in the ways of stagecraft. Most importantly, he understands how learning to perform can rebuild self-respect.

He’s got plenty of hardened dreamers to work with here. The group puts on a performance every six months, and the steering committee, with Divine G as a driving force, is pondering their next production.

Enter the volatile, unpredictable Sean “Divine Eye” Johnson, played by Clarence Maclin, actually a former Sing Sing inmate, in his first professional role. Casting non-professional actors can be tricky, but it’s what makes Sing Sing’s tale of redemption richly credible.

This movie stealthily undermines assumptions about men behind bars. The stone walls of Sing Sing by the end feel as though they can be scaled, first in the mind, finally in a determination to breathe free.

The semi-fictionalized story as scripted by Kwedar and Clint Bentley flings down a gauntlet for the small, dedicated troupe. The newbie shakes things up.

Tough, swaggering Divine Eye, whom we’ve seen darkly shake down another inmate, challenges the group to drop the “serious” plays they’re considering and take on a comedy. This feathery suggestion from a man who describes himself as a prison yard “monster”.

Let’s do it, says the group. From the jump, the storytelling is deliberately “theatrical” – that is, it’s about the craft of putting on a show, teaching men to be disciplined troupers in the art of theater.

Brent (Paul Raci, left) shows his band of inmate actors the healing power of making theater

Brent leads inmates through performers’ exercises, from walking, talking and dancing in a range of moods, to simply closing their eyes and imagining a lost friend or a blissful landscape.

He knows that such shared imagining bonds the participants, one of RTA’s profoundest aims.

Brent is a fast-typing writer of scenes and sketches, and, after gathering suggestions from the group, over a weekend he comes up with a full-length comic performance piece.

It uses time travel to stitch together group members’ fancies. The hodgepodge includes cowboy shootouts, visions of Kings of Egypt, a wildly roaming Freddie Krueger, even a dip into the To be or not to be soliloquy from Hamlet.

Incongruously, that particular brief sampling of Shakespeare falls to the bitter, cynical Divine Eye, who still isn’t sure this acting bs is worth his time. But Colman’s Divine G mellows Divine Eye’s hair-trigger temper, showing him how rage, channeled, can help turn a convict into an artist.

As it happens, the snarling Divine Eye is also up for a parole hearing, which means he, too, stands a chance of walking out of Sing Sing.

Cool, calm Divine G, with his carefully acquired legal knowledge at the ready, offers to help the hard, obstinate Divine Eye to chill, focus on the upcoming parole interview, and maybe win the remainder of his life that he’s dreamed of.

Domingo and Maclin, fully immersed in their volatile characters, pull off an acting showdown, too. These two wily inmates parry and joust with words, trying to game out each other’s moves — or cons.

The slightly older Divine G has been in the RTA program for years, minutely parsed his own emotions, learned to call them up to enact characters. Domingo’s task is to show us the trembling man underneath whose sculpted theatrical “triumphs” aren’t quite enough to keep his hopes for release alive.

The 25-to-lifer is in a long-delayed crisis. Hope can’t be “acted”. Either you have it, or you don’t. And you may need help from others to buoy it.

The street-hardened Divine Eye is in a different fix. He has to pivot from closed to open. Tossed into a theatrical setting, where feelings are flung around like confetti, he confronts something new: raw, unpredictable exposure. From an early age he took on the guise of a gangster, and he has no idea how to let the fierce protectiveness go.

In making art – a whole new concept for him – he becomes vulnerable. Nothing has prepared him for that. Acting gets him wondering if he can begin to dismantle the walls around himself.

These two performances, where masculinity drops its tough-guy front, lift Sing Sing above even its noblest intention, which is to show us hard men transformed into astonished artists, in touch with roiling feelings that can’t, and should never, be chained.

Domingo and Maclin also become men who learn mutual respect, offstage, out in the prison yard, opening up person to person, man to man.

This movie stealthily undermines assumptions about men behind bars. The stone walls of Sing Sing by the end feel as though they can be scaled, first in the mind, finally in a determination to breathe free.

Get in touch with that deathless instinct, the movie insists, and even if you stay inside, as nearly all the men we meet here do, prison needn’t lock down your spirit, or hold permanent sway over who you are or can become.

Life-affirming as that message is, we know from books, studies and articles that prison realities deny this path to tens of thousands of inmates, and this movie doesn’t grapple with that soul-crushing reality.

Racism, prison rape and gang culture, for instance, never come up. Hopefully future movies will tackle those horrendous systemic wrongs.

Last year around this time the movie Past Lives opened, and I was so moved and impressed by it I called it my Movie of the Year, hoping Oscar’s Best Picture award was in its future. Then, along came Oppenheimer and I had to acknowledge that as the greater achievement.

Nearly six months remain in 2024, so another movie may come along that for me will surpass Sing Sing. Possibly. But that movie has a dauntingly high wall to leap over.