Mad About the Boy: The Noël Coward Story (2023)

This documentary basks in the playwright/actor/songwriter's indelible charm

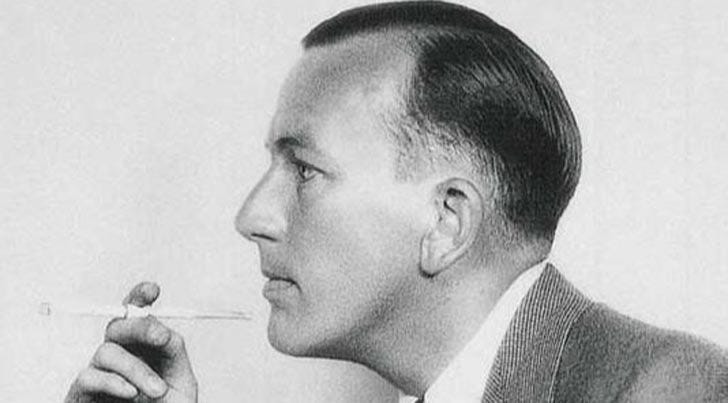

Coward’s easeful sophistication was at once dashing, impeccable and inexplicably hypnotic

Mad About the Boy: The Noël Coward Story (2023)

In theaters

Noël Coward (1899-1973) was a much-loved English entertainer who embodied his country’s character yet never felt entirely at home there. This documentary, directed with a dexterous light touch by Barnaby Thompson, takes great respectful care of its subject.

The movie’s discreetly unobtrusive narration is by the actor and writer Alan Cumming. Coward’s own scintillating words are tidily enunciated by the actor Rupert Everett.

They both let Coward’s droll wit shine. This movie is both a smooth visual pleasure and a rich listening experience. Words were Coward’s instinctive weapon of choice.

He was an entertainer from age two. He came from a poor background yet thrived due to a certain British doggedness (“Mad Dogs and Englishmen” is one of his funniest, most cheerily nationalistic, songs).

He wanted not just to laud the upper classes but to create a sleek, glamourous image of them – for them, as well as for those who ogled and envied them. He did. Winning their fond admiration and making himself world famous. It turned out that everyone, even in the lower orders, wanted an inside look at posh British easy living.

He wrote 60 plays, hundreds of songs, voguish short stories and sprightly music revues to get the word out, and he smartly never claimed the task was complete.

His beginnings weren’t promising. We see him in photos in his teenage years looking every inch the young English gentleman. In reality his devoted mother Violet ran a boarding house, scrimped and sacrificed to ensure his appearance was always elegant and bemusedly self-assured.

When he showed a fondness for music and performing, she pledged total support as long as his singing, dancing, acting and writing – all of which he’d rigorously undertaken by age 11 – were beyond reproach. He tells interviewers that her high standards guided him all his life.

But his rise was plagued by a lingering insecurity. He had no formal education, and, a voracious reader, was completely self-taught. His polish wasn’t bestowed but steadily acquired. He became debonair not through breeding but because getting it right was how he got on.

Why the pressure? The fact was, neither inherited wealth nor entitled birth gave him entree to the clubs and drawing rooms of the elite. To be witty and charming were his only inroads to winning upper class Britain’s favor.

And win it he did, spectacularly, through his playwriting and his chiseled savoir faire. Conquest, though, was gradual. After acting successfully in minor roles as a teenager, he crafted plays that were respectfully received but didn’t entirely dazzle London’s theatrical establishment.

Where, finally, was his home? Where was he most at peace? England produced him, gave him enormous success and nourished his keen eye and ear for both the incongruous and the delightful. But his home country wouldn’t allow him to be entirely who he was.

Then in 1924, at age 25, Coward struck gold with The Vortex, a play centered around cocaine addiction that was both shocking and fascinating to English upper-class playgoers. Here were people who spoke and dressed as they did but got into the most dreadful scrapes and hatched clever, disarming alibis when found out.

This combination of poise and perversity proved irresistible to audiences, and with a smash hit on his hands Coward found the courage and eventually the financial backing for his plays to take the British stage by storm.

The hits kept flowing from his pen, including Cavalcade (1931; its movie adaptation won the 1933 Oscar for Best Picture), as well as Fallen Angels and Hay Fever (both 1935).

He acted in many of his own plays and after the curtain fell was a much sought after man about town. He also became in the 1930s the most highly paid playwright in the world.

But something in this rise to theatrical heights was amiss, simply didn’t fit. Coward was homosexual, but could never reveal that fact, however many theater folk and socialites surmised or actually knew it.

It made profoundly good sense to stay, as we’d say today, on the down low. Homosexuality in England was a crime which if exposed could mean years in prison. Over his lifetime Coward had a few long-term relationships with men, without ever acknowledging his sexual orientation publicly.

But sexual fluidity had been worked into his plays in light, teasingly indirect ways nearly from the beginning. And they took on a more piquant flavor in two of his most enduring hits.

1932: Coward’s sparkling revue “Words and Music” featured his song “Mad About the Boy”

Private Lives (1930) is about a divorced couple who’ve married other people yet find they still care for one another. Design for Living (1932) features two playboys fond of an elegant woman who has trouble deciding between them, so she cavorts with both. Coward starred in both plays and won a fervent following.

These triumphs feature upper class sophisticates who nimbly wriggle into and out of relationships. This was precisely the kind of freedom of affectional preference that Coward wanted for himself but had to disguise.

So, he transformed a hindrance into fizzy comedy, and his plays’ infectious laughter made the risks of not playing by the rules feel liberating, jubilant. The playwright’s secrets slithered, camouflaged, under the froth.

Coward also wrote and directed (or co-directed) movies. Two have become classics. In Which We Serve (1942; written by and starring Coward; co-directed with David Lean) was a patriotic call to service that deeply stirred the British public.

1942: Coward (r.) inspired the British public as Naval Capt. Kinross in “In Which We Serve”

Brief Encounter (1945; written by Coward, directed by Lean) was a slightly pre-war love story starring Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson. Given its release date at the close of the conflict, it made the fragility of wartime relationships palpable and moving to a weary public.

After WWII Coward wrote songs and revues, had still more plays performed in Britain and America, and even made a financial killing singing some of his most intricate and refined songs in, of all places, Las Vegas.

Yet where, finally, was his home? Where was he most at peace? England produced him, gave him enormous success and nourished his keen eye and ear for both the incongruous and the delightful. But his home country wouldn’t allow him to be entirely who he was.

He spent his final years, blissfully by all accounts, in Jamaica, free from the entertainment whirlwind, and able to relax and express unconditional sexual passion, without any pressure to project an image of the contented bachelor.

He famously said he merely had a talent to amuse. Actually, across the years he developed the courage to counter rejection with wit, and the ingenuity to outmaneuver intolerance with laughter.

This documentary will prove especially helpful to those new to Coward and his work. It gives him his due but doesn’t cast him as any sort of societal “hero”. He was a complex man with an artistic lightness of touch and staying power that haven’t diminished.

In an interview Dick Cavett asks Coward where the essence of a successful artistic career comes from. Coward’s one-word answer: “Talent”. Take that, cruel – and deliriously silly – world.

A treat to arrive at the theatre and see you there! Great seeing it with you!